"I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ,

think it possible that

you may be mistaken."

Oliver Cromwell

In the manner of Plato's Dialogues

In conversation with a friend once, it emerged that I believed in the existence of God.

"But how can you?" she said. "I know you to love science, and you are not a religious man, and surely science is getting closer and closer to explaining everything without any God, and the day is coming when God will be proven as completely unnecessary. And then, will it not be like believing in fairies?"

I replied, "Well, without accepting your premise that science is getting closer to proving God unnecessary, if that were to happen, I would accept it, and I would stop believing that God exists."

"Ah!" she said. "So there is a tiny bit of doubt."

I said, "No, there is no doubt."

She looked perplexed.

"Let me explain it to you: I know who my mother and father were. Without the slightest doubt. I have seen enough to be absolutely sure. I have heard so many stories. I have been surrounded, all my life, by people who cross-referenced and verified those stories. There are parts of my body which I recognise as coming from one of my parents or the other. I have inherited certain abilities which can be attributed to them. There is no reason for me to doubt - I would be paranoid or a bit stupid, if I did.

"But one day there is a knock on the door and a pair of respectable people come in and tell me, 'We have some important news: We have found your real biological parents and it was not who you think... and here is the evidence.' And they produce that evidence, whatever that might be, not just DNA, and I put it to the test, and I cannot deny it.

"In that case, I will accept that I have been mistaken all my life and I will admit reality."

For me, phrases like 'Do you believe' and words like 'doubt' belong in the school playground when it comes to such profound questions. Because I know I am a human being and therefore I have a brain which can never be absolutely certain that I have reached ultimate truth about anything. Yes, I am sure about a lot of things, but always open to the truth.

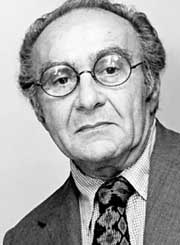

A Personal View - In the manner of prof. Bronowski

My friend would have benefited from considering how human knowledge is littered with more discoveries of its own previous errors than discoveries about the real world. Most recently, we have made proven cosmological discoveries which contradict every cosmological principle previously 'proven', i.e. we discover things which 'could not possibly exist.' And this is just one example. For thousands of years we believed the earth was flat and the sun went round it, despite eminent cries to the opposite as early as the Greeks. Then we believed in alchemy, we burned so-called witches, later still we searched for ether, we then thought Newton was the final word in astronomy and gravity, and Einstein rejected quantum physics. We are not that clever, are we?

This will not be surprising to some minds such as regular readers of this website. And the further we look into the future, or into the past, the less certain we can be about our 'beliefs', scientific or otherwise. We give more examples of this in our Evolution page. Dogma is the enemy of truth, whether religious, scientific, political (horror of horrors), legal, medical, or in any human endeavour. Those who claim to have absolute knowledge of anything are the most ignorant.

Plato's Republic gave us the analogy of prisoners in a cave able to see only shadows of the real things. Today humanity are no longer slaves chained to ignorance; we value searching, enlightenment, questioning, education and we have accumulated vast amounts of knowledge about the universe, including the natural world on earth and ourselves. But, for the most enlightened, this knowledge has come with a realisation of how little we do know and how much we do not.

Where do we draw the line, then, if we cannot be absolutely, rock solid sure about reality? Is there a line? Should we doubt that water consists of H2O, and all that physics and chemistry have demonstrated? Ah, that playground word 'doubt' again, or indeed our own expressions in this paragraph like 'draw the line,' language which prejudices our search for truth.

Is it legitimate, however, to explore whether we can find The Limits of Human Wisdom, or indeed to know our certainties, if any?

We know what H2O means at atomic level, and we know the properties of water, at least some of them, but do we know how the number and position of electrons and their orbits correspond to each property of water, its freezing and boiling points, its memory and so on? How does this work? Two different elements join up at atomic level to create a molecule with different properties to either of the two.

In his 1973 book The Ascent of Man professor Bronowski  made

the same argument on the limits of human wisdom using quantum physics

as his evidence. For example, he explained Heisenberg's Principle of

Uncertainty on the nature of elementary particles (e.g. photons, electrons)

to illustrate how the universe is constructed in a way we can never be

sure about (almost) anything regarding the world we live in, and must

be cautious about our own beliefs, especially as to our fellow humans

- a valid argument.

made

the same argument on the limits of human wisdom using quantum physics

as his evidence. For example, he explained Heisenberg's Principle of

Uncertainty on the nature of elementary particles (e.g. photons, electrons)

to illustrate how the universe is constructed in a way we can never be

sure about (almost) anything regarding the world we live in, and must

be cautious about our own beliefs, especially as to our fellow humans

- a valid argument.

"The world" he tells us, "is not a fixed array of objects." He quotes Uncertainty, as in the quantum world. Light behaves as a particle and as a wave. Particles are also quantums of energy, their orbits waves of probability. Strange, because it is contrary to our experience, but true. Nothing is fixed.

Likewise, we ourselves change constantly, we are not fixed in time. By the time you finish reading this, you will have aged imperceptibly - a good thing, if it confers knowledge and wisdom. There will be new interconnections in your brain, possibly new neurons also, made up of molecules, atoms, particles.

We explore the meaning of this in The Arts in General as it applies to how we see the world. Science has no monopoly over our efforts to see the truth. Sometimes art gets closer to representing reality. Art often reveals much more, whether in paintings, novels, music, theatre and so on, because it is better at uniting multiple points of view. It is not superior or inferior to science, we need both.

And so the professor's illustration does not only work at atomic level, but at other levels. He was right to expand the thesis into, ultimately, how we deal with each other as human beings and should be more tolerant and forgiving, never presuming we can see the whole truth.

But then he used the same argument to justify his belief (i.e. with certainty) in evolution as the process by which, what he called, 'Nature' brought forth very complex things like human beings.

And so, in the same breath, he committed the same error of judgement he was cautioning against, negating his own thesis regarding our inability to know absolute truth. He was, of course, right the first time.

I want to return to this in a moment but first, to support his basic understanding of our human limitations, I want to use a much simpler illustration. Because my own position is that the complexity of our world constitutes evidence, not of random events like evolution, but of greater intelligence, in other words that it is complex for a reason.

Imagine two identical cars. Absolutely the same in every way, even the colour, any wear and tear, etc. etc.. The only difference between them is that one has a manual gearbox and the other is automatic. Which of these two cars is the more complex in its totality? It is, of course, the automatic. Now let me ask a very different question: which is the simplest to drive? Once again, it is the automatic. So the more complex car is the simplest to use.

In the same way our world demonstrates the complexity it does so that everything works 'on automatic', without anyone's intervention, and we do not need absolute knowledge of its mechanics to live in it. We can just live our lives without wondering, for example, whether to trust the information we receive from the trillions of photons surrounding us, without knowing how our eyes work, and picking things up to eat without studying the chemistry of every bite we intake or how our body will deal with it. Even animals do the same with absolutely zero knowledge of chemistry or their own internal organs. Humans, plants, animals need no absolute knowledge to survive in this universe, on planet earth; but in order to have this simplicity of use, the laws that govern it are extremely complex. And all forms of life, including humans, can produce babies without having the foggiest of how it happens.

Professor Bronowski was a brilliant man in a very specific way, like all our individual brains. But, by his own thesis, no matter how brilliant one is, one will always be limited by one's human brain. In this instance, the professor's brain underestimated the complexity of our world, e.g. the human brain, despite admitting the limitations of science as well as his own.

Science, he tells us, aims to give an exact picture of the material world, which is unattainable. Errors cannot be taken out of scientific observation. There is no absolute knowledge. "Every judgement in science stands on the edge of error."

Complexity and beyond

In the case of quantum physics or biology, just because we have understood how something works at a certain level, i.e. understood the process, does not mean we have seen its true complexity at every level. There are many levels and, as humans, we can only go up (or down) to a certain level. We know how a sperm and an egg combine to conceive a baby, we understand the chemistry and the mechanics but, as in our example of H2O and the properties of water, do we even know how this new, unique DNA performs the millions of instructions necessary to end up with a brand new human being? 'How' being the crucial word, meaning exactly how.

Furthermore, there is the question of complexity, not of the world we live in, but of our own brains. The more complex the inquiring brain, the higher level of explanation it will demand.

Just as I was asked, at the top of this page, people often ask each other, 'Do you believe in God?' But the question can mean different things: Do you believe in God, i.e. that God exists? Or, Do you believe in God, i.e. that God will help you when you get into trouble? Which is a very different question. Or, Do you believe God hears prayers? It could also mean, Do you believe that God created everything, or that God made it what it is today, a distinction easily missed; or Do you believe that God intervenes, or that God plays dice with the universe, to quote Einstein, and so on. The difference is important, and better brains invented philosophy, not to give an answer so much, but to clarify the question.

So there are limits to human wisdom, but also limits to each one of our brains. There are brains and brains. At the low end there are those who fall in love 'because he likes Prosecco' (a certain brand of fizzy wine.) Further up the scale, people choose spouses with absolute certainly (they fall in love) on the basis of looks alone, and others because of 'personality', which may be a bit better. But have any of them understood the sheer complexity of another human being, in other words, how many elements make up that person, how many aspects there are to someone? They are about to find out.

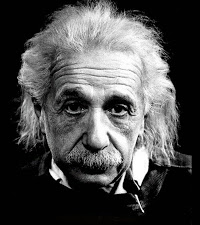

That was just an illustration. There are simple minds, ordinary commonplace minds, there are Prof. Bronowskis and there are brains able to go beyond technical knowledge, better constructed to see the bigger picture. Einstein's brain was one. He saw certain concepts, "not by maths but with insight and imagination" (Bronowski's words), what Einstein himself called 'thought experiments'. We have had glimpses of brains better (different) even than Einstein's. Some of Einstein's theories are being proved now, years after his death, but he still had difficulty with quantum physics. Some of his contemporaries did better than him on this.

Even Einstein underestimated the complexity of our world. But the difference is, I suspect, that he knew of his own limitations, probably the reason Einstein often mentioned God in the context of physics, as in "God does not play dice with the universe." And of course, God does not, except that the universe is constructed to be capable of infinite probabilities, closer to an automatic, rather than a manual car. Hence Einstein's difficulty in grasping the quantum world.

There are brains better at detail, and others better with vast concepts. There are those better at thinking in the abstract, and those who insist on the concrete. All of us find it difficult to conceptualise the strange, counter-intuitive quantum world, things that happen inside our bodies, and none of us will ever be able to see ultimate complexity.

Instead of belittling the outcome in order to deny its true complexity, we can focus first on what we see as the outcome, e.g. how improbable the odds against trillions of atoms interconnecting to form a human brain, and then ask whether we can truly grasp what makes it such. Brain surgeons indeed tell us we may never understand the brain. We certainly do not understand it now, except that, we are told by others, it came to be by a series of chance events.

Professor Bronowski agrees that the chances of atoms coming together to form himself and his brain were zero - the word he uses is "impossible". But, he tells us, "that's not how nature works..." that it happened step-by-step, gradually. Nature, he says, forms atoms, then molecules... Agreed, but then he extrapolates a process which can still be observed today, to continue with "...amino-acids and proteins forming living organisms and ultimately him", which is anything but demonstrable. To lump the two together in one sequence, in the same sentence, is intellectual dishonesty, unwitting though that may be. The leap from atoms and molecules to a brain with a cerebrum, a cerebellum, a cerebral cortex, a brainstem, a limbic system with the thalamus and hypothalamus, the amygdala, the mamillary bodies, the hippocampus, the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the pineal gland, the corpus callosum and so on, before we even come to the other organs of the body and how the brain controls those - this gap is so immense, we cannot let the professor bridge it in two small jumps. This is not a sequence as he claims. No such sequence exists, except in words. That is much more like believing in fairies, beautiful tale though it may be.

The limits of human wisdom tricked professor Bronowski into explaining away the human brain by stating it was possible for it to have evolved, if that happened gradually; cosmologists explain away the cosmos by inventing imaginary multiple universes, and others blindly accept such explanations rather than admit to our ignorance.

We know there are many levels of complexity and, ultimately, the universe is vast beyond our reach, and life on earth is infinitely complex, but our human brain can only grow so many neurons and synapses within our physical scull, it can only live to a certain age before it deteriorates and dies, it can only acquire knowledge and experience of the world during that short lifespan. And even that knowledge and experience is fallible, just as the professor tells us time and again.

This is how we should know there are limits to human wisdom and our ability, or inability, to see complexity. But there is also a practical test.

Professor Bronowski gives a very good explanation of how DNA works. I would now offer any scientist whatever he asks of me, if they could then construct a DNA molecule from scratch, from chemical elements, then place it inside a simple cell able to multiply, divide, differentiate and form a living plant or animal, let alone a human brain. We know what chemical elements it consists of, we know the structure, we know how DNA works, but that is completely different from seeing its true complexity.

And why use a ready-made living cell? Let them make that as well - after all, we know how it works.

What is the obstacle? The obstacle is complexity. And I would argue that those who propose it happened gradually are simply blind to its complexity. We are not arguing for the existence of God here, that is a separate, very different question. Only whether our human brains can truly grasp ultimate complexity.

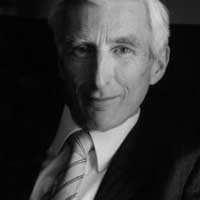

Professor Martin Rees (astronomer Royal and

fellow at Trinity, Cambridge) expressed the same thought when talking about our cosmological

theories and their difficulties, saying "Maybe there is a theory

[that explains our cosmos], but we are no better able to understand it

than chimpanzees."

expressed the same thought when talking about our cosmological

theories and their difficulties, saying "Maybe there is a theory

[that explains our cosmos], but we are no better able to understand it

than chimpanzees."

If there is one thing we should be able to say with certainty, it is that, all this technical knowledge and our understanding of astrophysics, quantum physics and molecular biology, show us that true complexity is far beyond our grasp, that we have not been able to see true complexity, not seen the whole truth and therefore not seen the truth.

When Einstein formed his General Theory of Relativity, one of

the conclusions was that the universe was expanding. This went against the

prevailing wisdom and against his own fundamental belief that the universe

was stable, in a steady state. So he introduced in his equations something

he called the cosmological constant, represented by the Greek letter lamda,

to stand for something unknown, a force which held the cosmos together.

conclusions was that the universe was expanding. This went against the

prevailing wisdom and against his own fundamental belief that the universe

was stable, in a steady state. So he introduced in his equations something

he called the cosmological constant, represented by the Greek letter lamda,

to stand for something unknown, a force which held the cosmos together.

Even when Georges Lemaître put the argument to Einstein directly for an expanding universe, Einstein told him his maths were good but his ideas abominable.

It is well known that, later, Einstein came to call this his biggest blunder. Edwin Hubble showed that the universe was expanding and so Einstein removed lamda from his equations. But the point here is, even the most intelligent of human brains are blinkered, no ifs, no buts, no exceptions, and not only on issues they know little about but in their own expert field. We are not saying they can be blinkered, they are blinkered.

Years passed and cosmologists came to believe (discovered?) that the universe was not only expanding, but the expansion was accelerating and, long after Einstein's death, cosmologists today are looking for something called Dark Energy, to explain this. It seems to them there is an invisible force pushing galaxies apart against the pull of their collective gravity. But they have no idea what it is.

So, after Einstein had corrected his "biggest blunder" by removing lamda from his equations, scientists today have put it back, this time, not to explain what holds the universe together, but what is pushing is apart - this unknown, supposed dark energy.

In our Cosmology page BrainsNet.Net takes the position that lamda is wrong yet again - there is no such thing as dark energy. We may be wrong, of course, because we only have a human brain ourselves, but a lot of philosophical thinking has gone into this conclusion, and it was philosophy which, back in ancient Greece, gave birth to science and scientific truth as we know it today.

Speaking philosophically, we cannot propose an answer to this monumental cosmological riddle, but we can point out a number of syllogisms. The amount of dark energy, we are told, seems to be increasing to remain a constant proportion as the volume of the universe expands. On the other hand, energy cannot come out of nothing. On the other hand yet again, in quantum mechanics, it seems particles (energy in the form of matter) do come into existence out of nothing in space (they borrow energy from the future and create matter and antimatter which annihilate each other). On the fourth hand, this is not enough dark energy to explain the expansion of the universe.

Cosmologists agree there is something fundamentally wrong with the way we understand physics. Quite apart from dark energy, we have equally big problems with our 'invention' of dark matter. More on this under Cosmology.

Human wisdom will always be one step behind absolute truth - we are not designed to see anything except from a certain point of view.

Yes, it is possible that the universe is more or less steady now, the fourth reversal of common wisdom, if that occurs. It is possible that the red shift we are seeing has a different explanation. Those distant galaxies billions of years away were moving apart when the universe was indeed still expanding billions of years ago, if that is right. Do we really know what happens to light over vast, unimaginable distances? It is interesting, put a different way, that the closer to us the galaxy, the slower its speed away from us, and the one closest of all, Andromeda, is moving towards us. Not only that, but the effect of so-called dark energy suddenly appears around six to seven billion years ago, we are told, as if somehow it came into existence halfway through the age of the universe. Not a definitive position to take, and it is not advocated here as such, but a simple reminder of just how blatantly wrong science and scientists can be. Great minds agree on this, and we knew that, anyway.

Here is a much simpler example: Bodies bulge because they spin - the faster the spin the greater the bulge. The earth has a bulge, as it spins every 24 hours, while Venus, of similar size, spins only once a year so it is spherical, and Jupiter, which spins about every 10 hours, has the biggest bulge. So far so good. But the sun, also spins every 27 days and yet is perfectly spherical, something only discovered in 2012. And no possible explanation can be thought of as yet.

One more example for good measure: The question of how all this water, vast oceans, came to be on earth, is said to be a mystery. There is nothing like it on other planets. When Rosetta released Philae to land on Comet 67P/C-G, early results disappointed those who thought water had arrived on earth on comets - it was a different kind of water, containing a different isotope of hydrogen. Back to square one then.

We live in a wonderful universe of complexity beyond our understanding. Each time we think we have resolved a question, many more questions pop up.

Our knowledge of the world we live in, whether the earth or the distant universe, is truly vast, by human standards, but our ignorance is much bigger.

The Implications

When I hear a great pianist or see men walking on the moon, I often use the expression 'Amazing, man is a small god!' That may be so, but man is not God. We should never be blinded by our achievements into hubris. We can land spacecraft on comets and study galaxies billions of light years away, we can peer into the atom and write incredibly complex symphonies, we can write the works of Shakespeare and solve complicated equations but there are things we cannot do.

Quite apart from our limitations in our understanding of our world, there are two crucial abilities the human brain does NOT have: 1) we cannot govern other people, and 2) we cannot sit in judgement of others.

1) We cannot legislate for, or rule over other people because we cannot predict the future.

Apart from the basics, such as 'Thou shall not steal or murder' etc., statutes often inherited from antiquity, we always legislate in retrospect, and we do not know how a changing world will be availed by bad people to do bad things in the future. And that is why we constantly amend our laws, abolish laws, for ever make new laws. We never get laws right. When we make new laws, we go by what happened in the past, and still we have not stopped crime. People who suffer unjustly fight to overturn those rulers, only to replace them with something as bad and often worse. Protests, strikes, struggles and dissatisfaction are almost as common in so-called democracies, regularly replacing the governing party.

2) And the reason why we cannot sit in judgement of others is because we cannot read minds.

I have attended court many times as the primary eyewitness, and the courts never got the facts right, not even when they accepted my evidence. Every single time, the court failed to understand what had actually happened, often with tragic consequences. And the judges' arrogance always played a role in that. Perfect example of the limits of human wisdom which those judges were not conscious of.

We have miscarriages of justice constantly in huge numbers every day. Only the occasional headline case comes to light, but thousands of smaller cases never come to the news, and thousands more never come to light at all, the wrong remains unrecognised. We presume the courts got it right - that is their job, we say.

Under The Brain and Consciousness we give the example of how Japanese babies lose the ability to differentiate between the sounds R and L very early, because in the Japanese language there is no difference. Quote: 'If that's how early we begin to distort reality, the practical lesson is to be more aware of our biases, to be wary of our perceptions, and never presume we can see the whole truth.' The Ames room and other optical illusions also show how easily our brains can be deceived, even when we know we are being deceived. And this is the limit of our human wisdom.

The English patient

British Justice is reputed to be par excellence and I would agree that the system, i.e. the law itself and legal procedures, do not need to change much, but a number of things get in the way.

1. In my experience, most British judges, the ones I knew, are not that brainy anyway, before the limit of human wisdom is factored in. And those not bright enough try to disguise it by turning into aggressive bullies, compounding that impression. It would serve them better to conduct a hearing, as they are supposed, rather than a talking.

2. Our brains are riddled with so many basic beliefs and emotions which we never have time to test by logic. As well as personal prejudices, other than racial, gender etc., judges also carry our common cultural inclinations from their own background. One might think they go by the evidence particular to this case but, in fact, they make assumptions, often in good faith, based on such personal or cultural misconceptions.

3. Thirdly, there are judges, just like other human beings, who wilfully want to inflict damage, loss, pain and suffering on innocent people they do not like, i.e. those they dislike for no obvious reason, including 'Goody-goody two shoes' individuals, as they see it, or people brighter than themselves, on those 'with ideas above their station', and so on. Such judges are guilty of the same crime as the Nazis, convinced in their own minds they were doing the right thing, or indeed like parents who abuse their own children and inflict cruelty 'for your own good.'

4. There are even judges who do not know the law on basics, such as what constitutes a contract, or the status of certain legal documents. Conversely, judges who want to impress with their legal knowledge by making 'findings' contrary to the facts of the case, in full knowledge, which is a form of fraud and theft, as well as perverting the course of justice, just to teach the lesson of their superiority.

So the law and the written code may be one thing, but they are not being adhered to, judges feel at liberty to side-step it or even ignore

it. Worse still, existing legislation against Perverting the Course

of Justice is not being applied against officers of the court,

i.e. judges, solicitors, barristers or junior operatives. It is not even

being investigated within the system.

being adhered to, judges feel at liberty to side-step it or even ignore

it. Worse still, existing legislation against Perverting the Course

of Justice is not being applied against officers of the court,

i.e. judges, solicitors, barristers or junior operatives. It is not even

being investigated within the system.

In the British legal system we recognise the limits of human wisdom by having several layers of an appeals process. Judges and juries getting it wrong is the cause of endless appeals and applications - courts hardly ever get anything absolutely right. One may be lulled into a false sense that justice will prevail eventually, and often it does, but those of us who have experience of the system know that is not how it works in practice. The appeals process is just as tortuous and subject to error, often too painful to pursue, having been through the mill already, and requests for an appeal hearing are not always granted.

Victims often exclaim, 'I will go to court and I will say...' They underestimate the force they will face not to say it, or even to stop them speaking at all, if the judge is prejudiced or unsympathetic, and barristers able to manipulate the hearing.

For example, there are rules of evidence to prevent the case being prejudiced. But often this is used to do the opposite, to obscure and prevent the truth coming out. Barristers are very skilful at doing this, for example to obtain a conviction against innocent people, perhaps unwittingly, or to get their criminal client acquitted, and they succeed.

Also, according to law, all evidence must be tested in court. But this does not happen in practice. Evidence from expert witnesses, for example, is virtually accepted de facto, practically untested, and scrutiny applied to a very different standard, if at all. There is a culture of not disrespecting fellow-professionals by challenging their professional opinion. When an expert gets it wrong, and they do, others have a mountain to climb to prove the error. Not to mention perjured witnesses, like experts regularly paid for their reports and coming to rely on certain clients for that income.

Courts are supposed to be places for discovering truth, for those naive and unfamiliar with the process but, often, everything will be done to obscure truth.

The problem again comes down, not to judges getting it wrong, of course they do, the problem is that far too many judges trust their own judgement with such finality, they violate procedures and even violate the law to bring about a particular result, and thus perpetrate injustice.

The above only reflects a minority of court cases, civil or criminal, but it is a significant minority, worthy of concern. And the overall effect is that of low standards overall in British society, as it perpetuates ingrained British resentment to complying with rules, judges themselves seen as upholding this culture against what the law prescribes, i.e. regarding attempts at higher standards as beyond the necessary and irritating. So honest, law-abiding citizens do not always know how they stand.

And the more we try to eliminate injustice, the more complex we make the process, and therefore make it more liable to error.

In 2004 the European Arrest Warrant was introduced to combat criminals escaping to another country. Then one day in 2014 it was used against two parents because they wanted to escape a UK hospital imposing, yes imposing, (raising questions of consent, apart from everything else), an inferior treatment on their son for a better treatment abroad. And those parents ended up in prison in Spain. But the EAW was not used in January 2015 against Hayat Boumeddiene, the most wanted woman in France for terrorist offences, and she was able to fly from Paris, to Spain, then to Turkey and then through the border to Syria, while police were still hunting for her in France. Perfect example of human stupidity, no matter what the system, the law, or set procedures.

Those parents were imprisoned away from their sick child but were eventually vindicated when their son's health improved abroad, and the treatment they had sought abroad was subsequently brought to Britain. But every week, in Great Britain alone, several patients die as a result of medical practitioners telling them there is nothing wrong when there is, or denying treatment to patients they do not 'like', or the reverse, by treating non-existent conditions, or administering the wrong medicine, or administering the wrong dose of a drug, or violating set procedures, or removing the wrong organ, or leaving instruments inside the patient after an operation.

For my entire life I read, on a regular basis, how doctors misdiagnose serious illnesses for trivial complaints and send patients home to die shortly afterwards. Not only that, but second opinions, third even multiple examinations miss obvious symptoms. How can it be that after a century of scientific medicine, and after years of training an individual doctor, we have found no way to avoid these regular, monumental errors?

The law and medicine in general have conferred great benefits on mankind, but the consequences are the most tragic when such practitioners forget their own limitations and forget the limits of human wisdom.

© John K

Smyrniotis

London 2023