|

|||||||

| Thank you for visiting BrainsNet.Net. | |||||||

| Organic Form | |||||||

|

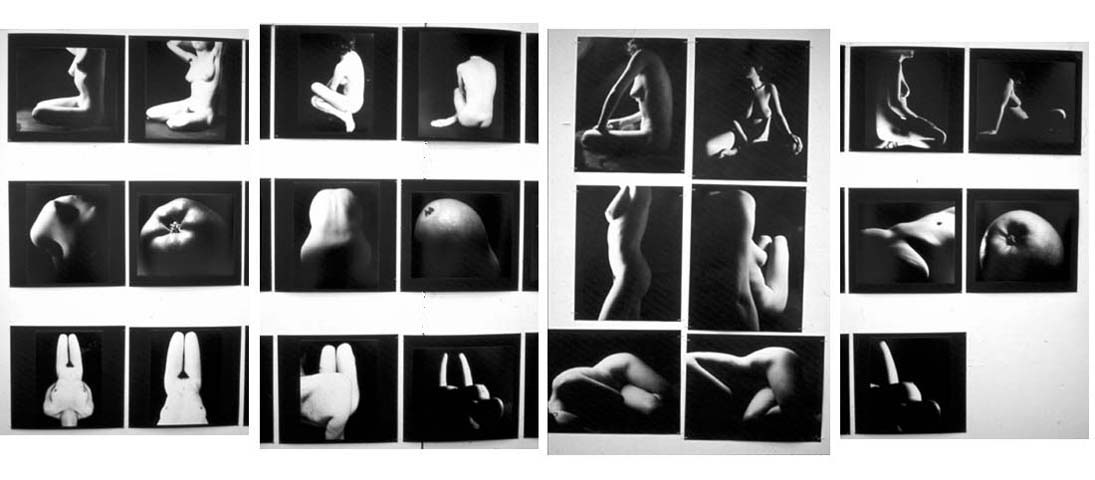

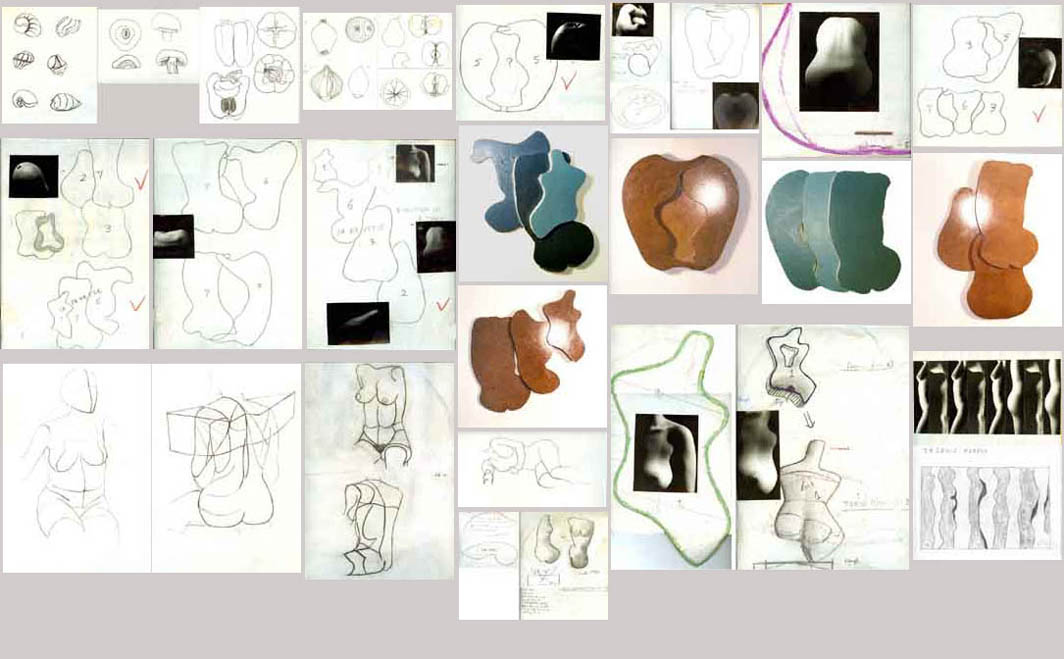

Studies by John

K Smyrniotis Firstly, Natural Form: The expression implies that forms found in nature are different from man-made forms. It also denotes that everything found in nature, whether plants, animals, or pebbles and mountains, are expressions of certain basic formulas. Rodin (figure right) expressed the belief in the following

words: "By following So, according to Rodin, similarities in form among such things as he mentions go beyond just accidental resemblances in appearance. Rather, the sameness lies in the principles according to which they were formed. This common formula should be manifest and can be found. I had attempted to do this in my own sculpture and photographic studies, relevant samples shown below. In nature, the form, and the surface that defines it, depend solely on what is underneath, the structure of the inside, which in turn depends on the object's function, whereas man-made objects display other considerations or limitations. Instinctively we recognise natural from man-made objects. The external differences between the two are due to the qualities which characterise their internal structure and the processes of their formation. These in turn depend on other principles. If we fail to observe the universality of Natural Form it is because of our familiarity, or presumed familiarity, with the nature that surrounds us, and it is the job of the artist to reawaken our consciousness to such differences. Fruit, trees, the human figure, stones, animals are so much part of our everyday environment that the eye no longer 'sees' them; it simply sees what the mind takes for granted, what it is told to see, dictated to by practical considerations. The problem therefore is to find a way to startle the eye, force it to take a fresh look over and above admiring a beautiful mountain, tree or woman. And one of the best ways to do this is to make the eye look in a specific way, under accurately controlled conditions and from a certain, perhaps unusual, viewpoint.

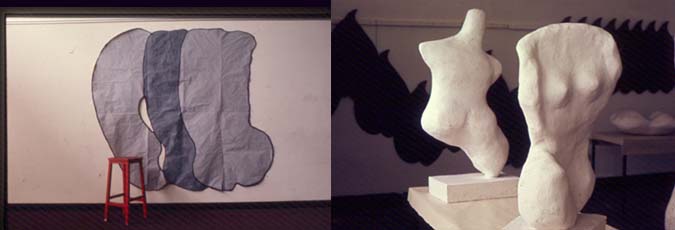

The need then arose to communicate my findings to others. I set out to try and reveal, through the camera and through sculpture, the universality of nature's formula and the principles applied to the making of Organic Form, and to create images by using such a simple vocabulary that the result would be abstracted.

I say this with trepidation because, as Brancusi stated, it is not the outward form which is real but the essence of things, and although form depends on function, it is impossible for anyone to express anything real by imitating surface appearances. Hence my attempt to simplify towards the abstract. I asked myself, what is it about it that makes it look organic, what is it that makes it recognisable as such to the intelligent mind? And the first step towards that goal was to become familiar with Organic Form first hand, through drawing and photography (examples below) until this vocabulary became part of my own 'language'.

ABOUT NATURAL FORM Professor C.H.Waddington (1905 - 1975): "If one found oneself walking along the strand of some unknown sea, littered with the debris of broken shells, isolated bones, and odd lumps of coral of some unfamiliar fauna, mingled with the jetsam from the wrecks of strange vessels, one feels that one would hardly make any mistakes in distinguishing the natural from the man-made objects…. Man-made mechanical forms, such as screws, cogs, propellers, are usually designed to serve one single function, or at most two or three, and their unity is correspondingly blatant and single-minded. The requirements of general living, for all but the simplest animals, cannot be reduced to performance of any series of actions." An army training manual on field-craft, essential to a soldier trying to detect camouflaged enemy objects, said that, generally speaking, regular patterns suggest man's presence while anything irregular is natural. This is a simplistic way of looking at things and not always true. Nature produces regular patterns such as leaves, while man can mimic nature for aesthetic or other purposes, or create irregularity by creating disorder. Even so, such patterns differ in their essential qualities.

Herbert Read, commenting on Jean Arp's work, said: "…

a form originally suggested by a bird or a shell can slowly be transformed

into a form suggesting a fruit or a cloud. This process of transfiguration

is based on a philosophy of nature, a morphology, which assumes

that all the forms in nature are modifications of a few basic forms,

a doctrine which Arp almost certainly took from Goethe." NATURAL AND ORGANIC At least two structural hierarchies are displayed in the universe: an inorganic and on organic. The first extends from clusters of galaxies, themselves arranged into super-clusters, to atoms and elementary particles, and the second from communities and single organisms down through organic systems, organs, tissues and cells to the molecules of which living organisms are composed. Consequently, the processes generating form in nature, i.e. by arranging parts to form new wholes, are different from the processes man uses and, hence, the products are bound to differ. There are several approaches to the study of form - the intelligent appraisal of mass with certain characteristics. Various artists have chosen different aspects, or different approaches to the same aspect. All approaches are a mixture of a subjective and an objective viewpoint. My definition of organic differs from that in chemistry. By Organic Form I mean the form of living things in their natural state, as opposed to other objects that may contain carbon, or the Natural Form of clouds, pebbles etc. All living things have the characteristics of a) reproduction and heredity, b) metabolism and growth, and c) innate ability to adapt to their environment. And all three imply the capacity to change from within. One might add d) a definite organisation and chemical composition. Whereas my distinction is clear, all art recognises that, visually,

there is no clear-cut boundary between organic and non-organic natural

forms. Already, we have seen comparisons between clouds, torsos,

shells and pebbles. In my own sculpture and photography,

however, I tried to concentrate on such comparisons as between the

human body and various fruits or trees, and even parts of the body

itself echoing other parts. © John

K Smyrniotis |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|

|

||||||

nature one obtains everything. When I have a beautiful woman's body

as a model, the drawings I make of it also give me pictures of insects,

birds and fishes. That seems incredible and I did not know it myself

until I found out… A woman, a mountain or a horse are formed

according to the same principles." One might add that Rodin

said as much again through his sculpture.

nature one obtains everything. When I have a beautiful woman's body

as a model, the drawings I make of it also give me pictures of insects,

birds and fishes. That seems incredible and I did not know it myself

until I found out… A woman, a mountain or a horse are formed

according to the same principles." One might add that Rodin

said as much again through his sculpture.

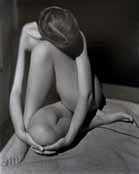

Photographer

Edward Weston (photos left) wrote: "Clouds, torsos,

shells, peppers, trees, rocks, smoke stacks are but interdependent,

interrelated parts of a whole, which is life. Life rhythms felt

in no matter what, become symbols of the whole."

Photographer

Edward Weston (photos left) wrote: "Clouds, torsos,

shells, peppers, trees, rocks, smoke stacks are but interdependent,

interrelated parts of a whole, which is life. Life rhythms felt

in no matter what, become symbols of the whole." This

is reflected in the work of such sculptors as Jean Arp, Henry

Moore, Brancusi, and others. Brancusi, in creating his Bird

in Space (right),was in search of the essential idea which, in his

view, constituted the

This

is reflected in the work of such sculptors as Jean Arp, Henry

Moore, Brancusi, and others. Brancusi, in creating his Bird

in Space (right),was in search of the essential idea which, in his

view, constituted the